COVER UP: How the DOJ Tried — and Failed — to Bury Trump’s Epstein Files

In May, Attorney General Pam Bondi told President Donald Trump that his name appeared multiple times in the Epstein files, according to The Wall Street Journal. By July, she declared the case closed. That choreography—warning first, absolution second—captures how power behaves when it wants a story to vanish: It doesn’t need to hide the truth; It only needs to declare the matter resolved.

That’s what the Department of Justice did this summer when it quietly issued its “case closed” letter on Jeffrey Epstein, assuring the public that every lead had been chased, every name examined, every stone overturned. But the 20,000 pages of documents Congress released on November 12 tell another story entirely. They reveal not a completed investigation, but a carefully managed retreat.

In hindsight, the DOJ’s language reads less like legal precision than narrative control: “This systematic review revealed no incriminating ‘client list’… We did not uncover evidence that could predicate an investigation against uncharged third parties.”

Exhaustive by what standard? And reviewed by whom? If the records released in November weren’t part of that review, then the Department wasn’t closing a case—it was closing its eyes. Or, more to the point, trying to gaslight the American people.

The newly surfaced files show Epstein’s correspondence extending long after his 2008 plea deal—emails about “moving her to Palm Beach for a few weeks” and “favors owed to VIPs.” In Epstein’s vocabulary, “favors” meant people, and “VIPs” meant men of power. What emerges isn’t just a rogue financier’s depravity but a network whose protection depended on its discretion.

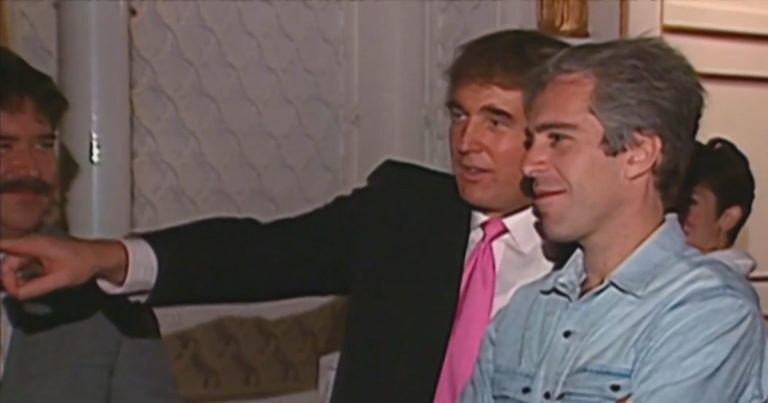

And of course, there is Trump. Despite his later insistence to Jonathan Swan and others that he “knew nothing” about Epstein’s activities, the record shows he was briefed in May that his name appeared repeatedly in the files. Oh, and by the way, Karoline Leavitt’s insistence that Trump kicked Epstein out of Mar-a-Lago because he knew he was a pedophile and creep? That’s at odds with Trump’s previous insistence that he knew nothing about Epstein, or even his wishing Ghislaine Maxwell “well” after she was arrested during his first term.

The “case closed” letter didn’t appear out of nowhere. It came under the direction of two senior Trump officials: Attorney General Bondi and FBI Director Kash Patel. Both had once spoken as if transparency about Jeffrey Epstein were absolutely their crusade. Patel, a Fox News regular before joining government, promised that releasing the hidden materials would lead to perp walks of powerful people. Bondi, during her time as Florida’s attorney general, had pledged to “get to the bottom” of Epstein’s reach and “let the public see everything.” But once they occupied the very offices capable of doing that, both reversed course. The people who had once demanded sunlight were now drawing the blinds.

By July, the DOJ’s letter arrived—citing an “exhaustive review” that found “no new prosecutable offenses.” Within weeks, Patel and Bondi were echoing the same message in public: there was “no list,” “no scandal,” “nothing new.” What had seemed like routine political messaging now reads as synchronized damage control. They weren’t responding to revelations. They were anticipating them.

The emails Congress pried loose weren’t hidden in foreign archives or sealed vaults. They were sitting, unindexed, in the Southern District of New York’s own digital files. The DOJ had claimed those materials were “redundant” to what it had already examined. That, plainly, was untrue. Its not clear if the Department was lying about what it found or lying about what it looked at. But evidence released on November 12 makes them look either incompetent, or complicit in a cover up.

Here is what we know about the timeline: In May, Bondi warned Trump that his name appeared in Epstein’s files. In July, the DOJ announced its “case closed” review. In November, Congress released 20,000 pages that the DOJ had never examined—pages that directly contradict the Department’s public assurances.

The missing piece is why Congress acted when it did. The November 12 release came after months of subpoenas and Freedom of Information lawsuits, but whether it was timed in response to the July closure or part of a longer calendar still matters. If it was the former, the DOJ’s July letter looks like an act of preemptive damage control—an attempt to define the story before the evidence emerged.

This wasn’t the cinematic corruption of shredded files and backroom deals. It was procedural, bureaucratic, almost banal. A letter here, a memo there—each step designed to create the impression of finality. The cover-up was quiet, methodical, institutional. It protected not just the president, but the Department itself. To reopen Epstein’s case would mean reopening the failures of those who handled it: prosecutors, investigators, political appointees. The reflex was not ideological but self-preserving.

Figures like Bondi and Patel had once railed against the “deep state.” Now they appear to have become part of it. The machinery they claimed to expose became the very mechanism they used to bury the truth.

Three questions now hang in the air: Who at the DOJ decided those 20,000 pages were “redundant”? What was the basis for the “exhaustive review” if those emails were never seen? And what communications, if any, occurred between DOJ officials and Trump-world figures while the letter was being drafted?

Until those questions are answered, “case closed” stands as an epitaph not for a criminal investigation, but for accountability itself. When power wants a story to die, it doesn’t need to bury the body. It just files the paperwork.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.